This week has been focused on position and positionality. We talk in open studio about the uncomfortableness of disclosing certain aspects of our identities – of ‘outing’ ourselves, specifically in the context of MAIP. Some things are more uncomfortable to talk about than others. Some feel more personal, are less evident without disclosure and also – sometimes – feel less relevant. We talk about the fear of being the odd one out, because we are the only one who shares, or because we’re the only one with this identity.

The conversation circles around sexuality. I’m listening as someone who identifies as heterosexual and has only ever been in heterosexual relationships. I wonder how this is colouring how I hear the conversation; how I interact with it. My instinct is to just listen and let others with lived experience lead the conversation. But I want to contribute to a positive, safe space – how do I do this?

The conversation highlights how disclosure of characteristics that are not evident should always be a choice. And that it’s important to consider the safety and mental wellbeing of the person in their specific context, not just their cultural and legal context, but family, social, personal, etc. As a group, we live in countries with vastly different cultural and legal views on sexuality. Somebody highlights how this spiralling conversation, which flows from sexuality into relationships, is sensitive and can be triggering for someone who has experienced sexual assault.

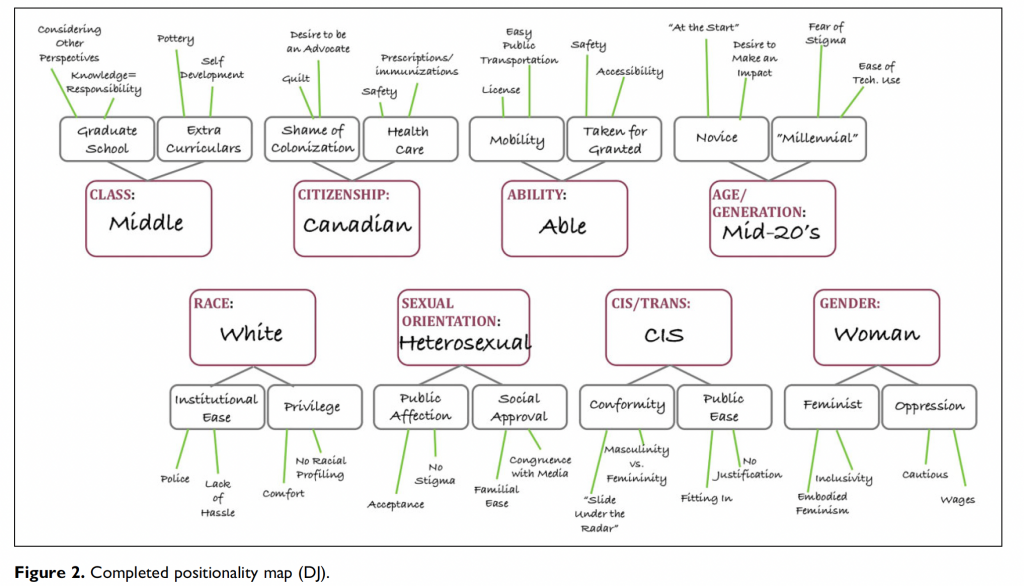

In class, we looked at Danielle Jacobson and Nida Mustafa’s ‘Social Identity Map’1, which is a tool for mapping our positionality. The identity markers on the diagram are cultural (from a Canadian perspective) and I raised the point that I might divide them differently. I invited those from different cultural backgrounds to share how the map differed from what they would include. I highlighted class, which led to a deep discussion, but what I failed to articulate clearly was my suspicion that in some cultural contexts there might be some characteristics totally absent, or new categories present. What might these be?

Through all this, I was thinking about my experiences of measuring people’s personal characteristics. This is work I’ve done in different contexts and for different purposes. As a journalist, I conducted research and reported on the research of others that used protected characteristics as the basis to measure and understand issues of diversity, equality and inclusion in the arts sector. This research shaped public policy and funding, and strategy and processes within arts organisations. While working for arts organisations, ‘equality monitoring’ was a tool to ensure we were working effectively and equitably in relation to our workforce, audiences and participants, and was part and parcel of delivering publicly funded projects. I used it to tell the story of artists’ work, in order to attract funding, and had to report on it as part of funding requirements.

The forms that funders required us to use were generally based on protected characteristics, although often elaborated and expanded in a way that reflected the cultural concerns of the time (for example around class – origin and destination class). Categories included religion, gender identity and sexuality. When we asked people involved with arts engagement projects – often people coming from different cultural backgrounds – to complete these forms, sexuality was a category that was often challenged; that caused conversation and discomfort. Or that people simply refused to complete. Why was who they are sexually attracted to relevant to their participation in this print-making workshop? It’s a good and valid question and one we grappled with.

I do believe that any characteristic/identity marker that is routinely used to oppress or discriminate within a context is relevant. And I also believe the expression: “What is measured is treasured.” It’s not enough to be aware of a problem – we need to understand the scale and scope of it, if we are to effectively combat it. Through the process of monitoring, we introduce a routine consideration of these problems that keeps them in mind, heightens awareness and aids positive action. It’s vital to identifying if practices for ensuring equality are actually working.

But it’s also impossible for me to know how it feels to be engaging in an activity like an arts workshop, and suddenly to be asked to declare something deeply personal about yourself, something that has potentially been a complicated source of fear, pain and discrimination, which you might have worked to keep secret for reasons of personal safety and wellbeing.

It feels obvious that a blanket approach to equality monitoring that ignores context and personal experience can do harm – possibly more so than it does good. Today’s discussion, for me, highlighted how sexuality is a particularly tricky area, especially when working interculturally. Personal and cultural contexts deeply affect the act of disclosure. Understanding the relevance of sexuality also requires a deep understanding of the context of a project. Its relevance and the effect of oppression/discrimination shift on a contextual and individual level – it can change over time and depending on evolving personal circumstances and intersectionality.

In relation to my arts management practice, my takeaway is that arts organisations in the UK need more agency to define what is relevant to measure and to respond to the context of their projects and communities in order to be sensitive to cultural nuances and individual lived experience.

1 Jacobson, D., Mustafa, N. (2019) ‘Social Identity Map: A Reflexivity Tool for Practicing Explicit Positionality in Critical Qualitative Research’, International Journal of Qualitative Measures, Volume 18, pp. 1-12.

Leave a Reply